Over the past year, I was pretty busy at my work.

I had issues finding time to practice on personal projects. Since I value the experience acquired by such projects, I chose an optimization problem on CodinGame to keep me motivated to learn new things.

I challenged myself to solve the Mars Lander game with a genetic algorithm.

Even though I acknowledged the popularity and usefulness of genetic algorithms, I always was reluctant to use them.

How I could use them to beat random searches and tweak their parameters was unclear.

I felt I would reconcile with genetic algorithms if I could reach 95% of the best score without domain knowledge.

Since the best score is 2509, obtained by FredericBautista, my target was 2383, around rank 114 out of 5258 players with 100% completion.

As this was the first time I coded a genetic algorithm, I needed to develop helper tools to understand its mechanism better, tune its parameters, and debug it. My action plan was the following:

- Validate the simulation of the game,

- Write a graphic application to debug and interact with bots,

- Write a Monte-Carlo Bot,

- Write a genetic algorithm,

- Iterate on my bot until I reach my target.

1. Validating the simulation

Mars Lander is about landing a vehicle (the lander) on a planet with gravity but no atmosphere (no friction or wind). The planet's surface is a 2D polyline, and the landing area is the single horizontal portion of that polyline. The lander has a rotation range and a rotation speed limit. The thruster of that lander has five levels of power, and it consumes fuel. To land safely, the lander must be perfectly vertical with limited horizontal and vertical speeds. If the lander crashes outside the landing area, goes outside the world boundaries, or runs out of fuel, this is a failure. To complete the optimization problem correctly, one must land on five different levels.

The referee simulates the state of the lander using floating point precision but provides integers as inputs.

It might seem overwhelming to write a valid solution, but it is pretty simple.

Since implementing an exact simulation is a requirement to implement search algorithms on CodinGame, I obtained that first step quickly.

To help people wanting to try this optimization game, I'll show a simplified version of my data structures and simulation code in this section.

First, let's start with utility code, 2D geometry classes, and constants:

# pragma once

# include <cinttypes> // to bring any integral type definition in the scope

# include <cstdio> // to bring all the c standard I/O function (faster than C++ ones)

# include <cstring> // memset

# include <cmath>

# include <chrono>

# include <string>

struct BotController {

char* _buffer = nullptr;

size_t _size;

using clock = std::chrono::steady_clock;

clock::time_point _start;

FILE* _file = nullptr;

BotController(FILE* file = nullptr) noexcept : _start{clock::now()}, _file{file}{}

~BotController() {free(_buffer); }

int32_t elapsed() const noexcept { return (int32_t)std::chrono::duration_cast(clock::now() - _start).count();}

void read_next_line(bool reset_timer = false) noexcept {

getline(&_buffer, &_size, _file);

if (reset_timer) _start = clock::now();}

template inline void parse(const char* format, const Args&... args) const noexcept { (void)sscanf(_buffer, format, args...); }

template inline void parse_with_offset(int offset, const char* format, const Args&... args) const noexcept { sscanf(_buffer + offset, format, args...); }

};

struct vec2 {

using Scalar = double;

constexpr vec2() noexcept : raw{0, 0}{}

constexpr vec2(Scalar a, Scalar b) noexcept : raw{ a, b }{}

constexpr vec2(const vec2& other) noexcept : raw{ other.raw[0], other.raw[1] }{}

constexpr vec2 operator=(const vec2& other) noexcept { raw[0] = other.raw[0]; raw[1] = other.raw[1]; return *this; }

constexpr bool operator==(const vec2& other) const noexcept { return raw[0] == other.raw[0] && raw[1] == other.raw[1]; }

constexpr bool operator!=(const vec2& other ) const noexcept { return raw[0] != other.raw[0] || raw[1] != other.raw[1]; }

constexpr vec2 operator-() const noexcept { return { -raw[0], -raw[1] }; }

constexpr vec2& operator-=(const vec2 other ) noexcept { raw[0] -= other.raw[0]; raw[1] -= other.raw[1]; return *this; }

constexpr vec2 operator-(const vec2 other ) const noexcept { return { raw[0] - other.raw[0], raw[1] - other.raw[1] }; }

constexpr vec2& operator+=(const vec2 other ) noexcept { raw[0] += other.raw[0]; raw[1] += other.raw[1]; return *this; }

constexpr vec2 operator+(const vec2 other ) const noexcept { return { raw[0] + other.raw[0], raw[1] + other.raw[1] }; }

constexpr vec2& operator*=(Scalar s) noexcept { raw[0] *= s; raw[1] *= s; return *this; }

constexpr vec2 operator*(Scalar s) const noexcept { return { raw[0] * s, raw[1] * s }; }

constexpr Scalar operator*(const vec2 other) const noexcept { return raw[0] * other.raw[0] + raw[1] * other.raw[1]; }

constexpr vec2& operator/=(Scalar s) noexcept { raw[0] /= s; raw[1] /= s; return *this; }

constexpr vec2 operator/(Scalar s) const noexcept { return { raw[0] / s, raw[1] / s }; }

constexpr Scalar squared_length() const noexcept { return raw[0] * raw[0] + raw[1] * raw[1]; }

Scalar length() const noexcept { return std::sqrt( raw[0] * raw[0] + raw[1] * raw[1] ); }

union {

struct {

double x;

double y;

};

double raw[2];

};

};

struct Segment2 {

using Scalar = vec2::Scalar;

constexpr Segment2() noexcept {}

constexpr Segment2( const vec2& p0, const vec2& p1 ) noexcept : origin{ p0 }, diff{ p1.x - p0.x, p1.y - p0.y } {}

constexpr Segment2( const Segment2& other ) noexcept : origin{ other.origin }, diff{ other.diff } {}

Segment2& operator=( const Segment2& other ) noexcept {

origin = other.origin; diff = other.diff;

return *this;

}

constexpr vec2 point(Scalar s) const noexcept {

return origin + diff * s;

}

constexpr bool intersects( const Segment2& other, Scalar& t ) const noexcept {

// NOTE: does not handle parallel lines

const Scalar denominator = - other.diff.x * diff.y + other.diff.y * diff.x;

const Scalar s = (-diff.y * (origin.x - other.origin.x) + diff.x * (origin.y - other.origin.y)) / denominator;

t = ( other.diff.x * (origin.y - other.origin.y) - other.diff.y * (origin.x - other.origin.x)) / denominator;

return s >= Scalar(0.0) && s <= Scalar(1.0) && t >= Scalar(0.0) && t <= Scalar(1.0);

}

vec2 origin, diff;

};

namespace constants {

static constexpr double gravity = 3.711;

static constexpr double degree_to_radians = M_PI / 180.0;

static constexpr double radians_to_degree = 180.0 / M_PI;

static constexpr double horizontal_speed_limit = 20.0;

static constexpr double vertical_speed_limit = 40.0;

static constexpr int32_t first_turn_response_time_microseconds = 1'000'000;

static constexpr int32_t response_time_microseconds = 100'000;

static constexpr double world_width = 7000.f;

static constexpr double world_height = 3000.f;

static constexpr double world_ratio = world_width / world_height;

} Next, let us see the command and output structures used to store orders and send such orders to CodinGame or local tools:

struct Command {

Command() noexcept : dthrust{1}, drotation{15} {}

bool operator==(Command other) const noexcept { return raw == other.raw; }

union {

struct {

uint8_t dthrust : 2; // 0 - decrease, 1 - keep, 2 - increase

uint8_t drotation: 6; // rotation is drotation - 15

};

uint8_t raw;

};

};

struct Output {

int8_t previous_orientation;

int8_t current_orientation ;

uint8_t previous_power: 3;

uint8_t current_power : 3;

uint8_t set : 1;

void initialize(int8_t rotation, uint8_t thrust) { previous_orientation = rotation; previous_power = thrust; }

void send(Command command) { send(previous_orientation + command.drotation - 15, uint8_t(previous_power + command.dthrust - 1)); }

void send(int8_t rotation, uint8_t thrust) {

CheckMsg(!set, "Sent multiple orders for the same turn");

CheckMsg(abs(rotation - previous_orientation) <= 15, "Rotation variation too strong: was %i before, requested %i", previous_orientation, rotation);

CheckMsg(abs(thrust - previous_power) <= 1, "Power variation too strong: was %i before, requested %i", previous_power, thrust);

current_power = thrust;

current_orientation = rotation;

set = 1;

}

void finish() {

CheckMsg(set, "Forgot to output an order");

if constexpr (is_codingame) {

fprintf(stdout, "%i %i\n", current_orientation, current_power);

fflush(stdout);

}

previous_orientation = current_orientation;

previous_power = current_power;

set = 0;

}

};Finally, here are the world structure and two lander state representations; one is rounded, and we will fill it from the referee inputs,

and the other one use floating point precision and will be used by our genetic algorithm:

struct World {

void initialize(BotController& controller, bool reset_timer) noexcept {

uint16_t x, y;

controller.read_next_line(reset_timer); controller.parse("%" SCNu8, &point_count);

segment_count = uint8_t(point_count - 1);

controller.read_next_line(false); controller.parse("%" SCNu16 " %" SCNu16, &x, &y);

points[0].x = x;

points[0].y = y;

for (uint8_t i = 1; i < point_count; ++i) {

controller.read_next_line(false); controller.parse("%" SCNu16 " %" SCNu16, &x, &y);

points[i].x = x;

points[i].y = y;

segments[i - 1] = Segment2{ points[i-1], points[i] };

}

}

vec2 points[30];

Segment2 segments[30];

uint8_t point_count = 0;

uint8_t segment_count = 0;

};

struct RoundedLanderState { // read from the referee, used to validate simulation

void load(BotController& controller, bool reset_timer) noexcept {

controller.read_next_line(reset_timer);

controller.parse( "%" SCNd16 " %" SCNd16 " %" SCNd16 " %" SCNd16 " %" SCNd16 " %" SCNd8 " %" SCNd8, &x, &y, &vx, &vy, &fuel, &angle, &power);

}

void display(FILE* file) const noexcept { fprintf(file, "p=(%i,%i) v=(%i,%i) fuel=%i angle=%i power=%i", x, y, vx, vy, fuel, angle, power); }

int16_t x, y, vx, vy;

uint16_t fuel;

int8_t angle;

uint8_t power;

};

struct Lander {

bool validate(const RoundedLanderState& state) const noexcept {

if (fuel != state.fuel || angle != state.angle || power != state.power) return false;

return (int16_t)std::round(p.x) == state.x && (int16_t)std::round(p.y) == state.y

&& (int16_t)std::round(v.x) == state.vx && (int16_t)std::round(v.y) == state.vy;

}

void display(FILE* file) const noexcept { fprintf(file, "p=(%f,%f) v=(%f,%f) fuel=%i angle=%i power=%i", p.x, p.y, v.x, v.y, fuel, angle, power); }

void load(const RoundedLanderState& state) noexcept {

p.x = state.x; p.y = state.y;

v.x = state.vx; v.y = state.vy;

fuel = state.fuel; angle = state.angle; power = state.power;

}

void update(int8_t rotation, uint8_t thrust) noexcept {

CheckMsg(abs(rotation - angle) <= 15, "Rotation variation too stong: previous=%i, requested=%i", angle, rotation);

CheckMsg(rotation >= -90 && rotation <= 90, "Rotation must be in [-90, 90] (value = %i)", rotation);

CheckMsg(thrust < 5, "Invalid power value: %i", thrust);

CheckMsg(abs(thrust - power) <= 1, "Power variation too strong: previous=%i, requested=%i", power, thrust);

angle = rotation;

power = thrust;

fuel = thrust > fuel ? 0 : fuel - thrust;

const double alpha = angle * constants::degree_to_radians;

const double ax = -power * std::sin(alpha);

const double ay = power * std::cos(alpha) - constants::gravity;

p.x += v.x + 0.5 * ax;

p.y += v.y + 0.5 * ay;

v.x += ax;

v.y += ay;

}

void update(Command command) noexcept { update(angle + command.drotation - 15, uint8_t(power + command.dthrust - 1));}

vec2 p, v;

uint16_t fuel;

int8_t angle;

uint8_t power;

};

You will find below the general structure of the bot.

The main entry point is the step phase to have a clean way to initialize internal data, but you could merge them into one.

Before sending the output to the referee, the bot applies the chosen command to the floating-point precision lander state.

When the referee sends us integer inputs, we can round the floating-point precision state and compare the result with inputs (see the checkSimulation method).

struct Bot {

void checkSimulation() const {

if(!lander.validate(rounded)) {

fprintf(stderr, "[SIMULATION] invalid simulated state at turn %i\n", turn);

fprintf(stderr, "Referee: "); rounded.display(stderr);

fprintf(stderr, "\nInternal: "); lander.display(stderr);

fprintf(stderr, "\n");

TRAP; // a macro that will stop the game on CodinGame with a report, and trigger a debugger locally.

}

}

void initialize(BotController &controller, Output &output) {

turn = 1;

world.initialize(controller, true);

rounded.load(controller, false);

lander.load(rounded);

output.initialize(rounded.angle, rounded.power);

act(controller, output);

}

void step(BotController &controller, Output &output) {

++turn;

rounded.load(controller, true);

checkSimulation();

act(controller, output);

}

int loop() {

BotController controller{stdin};

Output output;

try {

initialize(controller, output);

while (true) {

step(controller, output);

}

}

catch (const std::exception& exc) {

fprintf(stderr, "[CRASH] unhandled exception '%s'", exc.what());

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

void act(const BotController &controller, Output &output) {

const int32_t max_answering_time = (turn == 0 ? constants::first_turn_response_time_microseconds : constants::response_time_microseconds) - 1'000;

Command best = /* implement your own algorithm :-} */;

lander.update(best);

output.send(best);

output.finish();

++turn;

}

World world;

RoundedLanderState rounded;

Lander lander;

uint8_t turn = 0;

};By producing a random but valid command each turn and executing your bot on all levels on CodinGame, you can assess the validity of the simulation. Now you can write a local referee that triggers (in dev builds) a breakpoint whenever it receives an incorrect command. If you hardcode a set of commands for a given level, you can play it on CodinGame and your local referee to compare results. This process will validate your referee, which you will reuse to write search algorithms.

2. Writing a Graphic Application for Tools and Debug

Having a framework to add tools quickly, visual debugs, and display analyses on screen would greatly help me complete my challenge. I wrote an extendable application that can display the world, lander states, and trajectories, zooming and panning with the mouse and a customizable controls panel to map UI elements. I chose the nanogui library to write such a framework, as it is easy to install and quick to use. I wholeheartedly recommend you such a library for your bots.

Since I would need different modes for my application to perform various tasks, I coded them as sub-application: I subclass a base application interface to implement specific needs and register it with a name in a registry. When I start the application, I only have to provide the mode name to launch it. This system allowed for compact code managing shared functionalities and straightforward customization. Here are some of the modes I wrote:

- a world analyzer mode, used to test a metric for my evaluation function,

- a trajectories mode to generate, iterate, and analyze trajectories produced by my different bots (see the image below)

- a crossover mode to debug and validate parameters of the crossover computation for my genetic algorithm.

Even though I'm used to coding graphical applications, as it has always been my job, this framework took me some time since it's not fun to do. However, I can reuse it for future bots, so the return on investment will be alright. With that out of the way, I could entirely focus on completing my challenge.

3. A Monte-Carlo Bot with a Simple Evaluation

My go-to method for addressing a search problem is writing a Monte-Carlo bot with a simple evaluation. The principle is to generate random trajectories, rate them by an evaluation method, and keep the best one according to that metric. Doing so allows me to check if a search algorithm can solve a problem, assess what kind of evaluation method is required, and ensure a more complex search algorithm would improve the bot by allowing the search to continue for longer. Also, writing a Monte-Carlo bot is a low effort and could produce good results, thus helping to make progress and stay motivated.

My Monte-Carlo bot was able to solve the simpler levels and rarely able to solve others. From my analyses, I needed to carefully tune the landing phase and better guide the navigation phase to improve the bot. Doing so would require domain-specific knowledge to enhance a pure random Monte-Carlo bot. When granting the bot ten times the allowed time per turn, it landed successfully on four out of five levels more often. I was thus in a perfect situation to try a genetic algorithm:

- I could not improve my Monte-Carlo bot without domain-specific knowledge to guide the randomness,

- experiences showed that a more efficient search algorithm would perform better.

4. Developping a Genetic Algorithm

Since I was reluctant against genetic algorithms, the most efficient way to learn how to use them was not to study books or courses but to follow the excellent post by Di_Masta.

In this post, he describes how he solved the Mars Lander game with a genetic algorithm.

I read this post many times until it was clear how to implement my first version.

I encourage you to do the same: even without prior knowledge about genetic algorithms, you will understand how to use them.

Contrary to Di_Masta, I chose to have a dynamic chromosome length.

When building a chromosome, I have a lander state representing the current situation.

If the state reaches a terminal configuration (out of fuel, out of bounds, intersecting the surface polyline), I stop adding new genes to the chromosome.

I suspected this has led to many differences between our implementations as our results differed vastly.

The first version of my genetic algorithms incredibly outperformed my Monte-Carlot bot. It had many issues, but submitting it multiple times completed all five levels. The results seemed too good to be only caused by a genetic algorithm as simple and rough as mine. I double and tripled checked my Monte-Carlo bot but failed to explain the difference by bugs or mistakes. The numbers of iterations per turn were relatively high compared to those given by other players. So, despite having yet to make an effort to optimize my bots, I knew they were efficient enough to rule out a low number of iterations. I could not deny the power of genetic algorithms anymore; without domain-specific knowledge, I reached 71% of the best score with my first genetic algorithm bot.

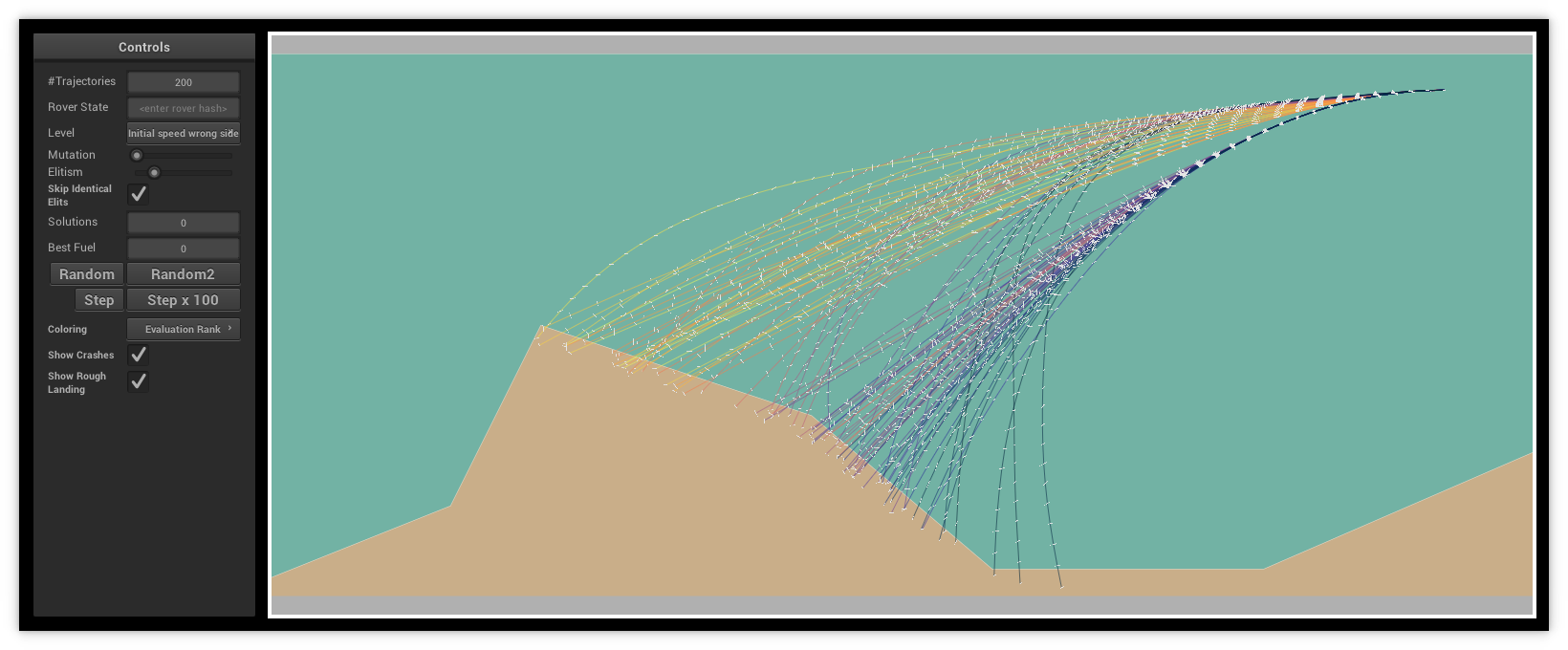

I wrote some analysis tools to display my trajectories and gather statistics about failures. They exhibited the following facts:

- very slow convergence,

- best chromosomes sometimes consumed more fuel than previous generations,

- many trajectories were packed together.

These facts pointed toward the evaluation function, which had many flaws. One flaw was using an extensive range of values; when normalizing evaluations for the crossover, floating point precisions produced wrong selection factors, messing with the ordering of chromosomes. Another flaw was separating trajectories into three categories, crashing, crashing on the landing zone, landing safely, and giving a different range of values for each type with distinct computation methods. After I fixed those flaws, tools indicated that most simulations crashed due to the lander not being perfectly vertical when hitting the ground. When the lander reaches the landing zone, I check if the evaluation score is better by modifying the last command/gene to orient the lander correctly. Then I did a small parameter optimization pass to identify a set of values that performed best. The resulting bot reached rank #100 with 2392 points. I was proud of myself, I completed my challenge. Still, I decided to pursue obtaining valuable experience in genetic algorithms.

| Score | Failures | |

|---|---|---|

| First genetic algorithm | 1 790 | 22.7% |

| + fixed evaluation | 2 113 | 5.2% |

| + fixed rotation & parameters optimization | 2 392 | 0% |

5. Final modifications

I tried to figure out how to improve my score by tweaking parameters or adding more complex steps to my genetic algorithm. I liked having only a few parameters and simple steps; it would be an excellent example for my future uses. So instead, I chose to apply my generic tricks.

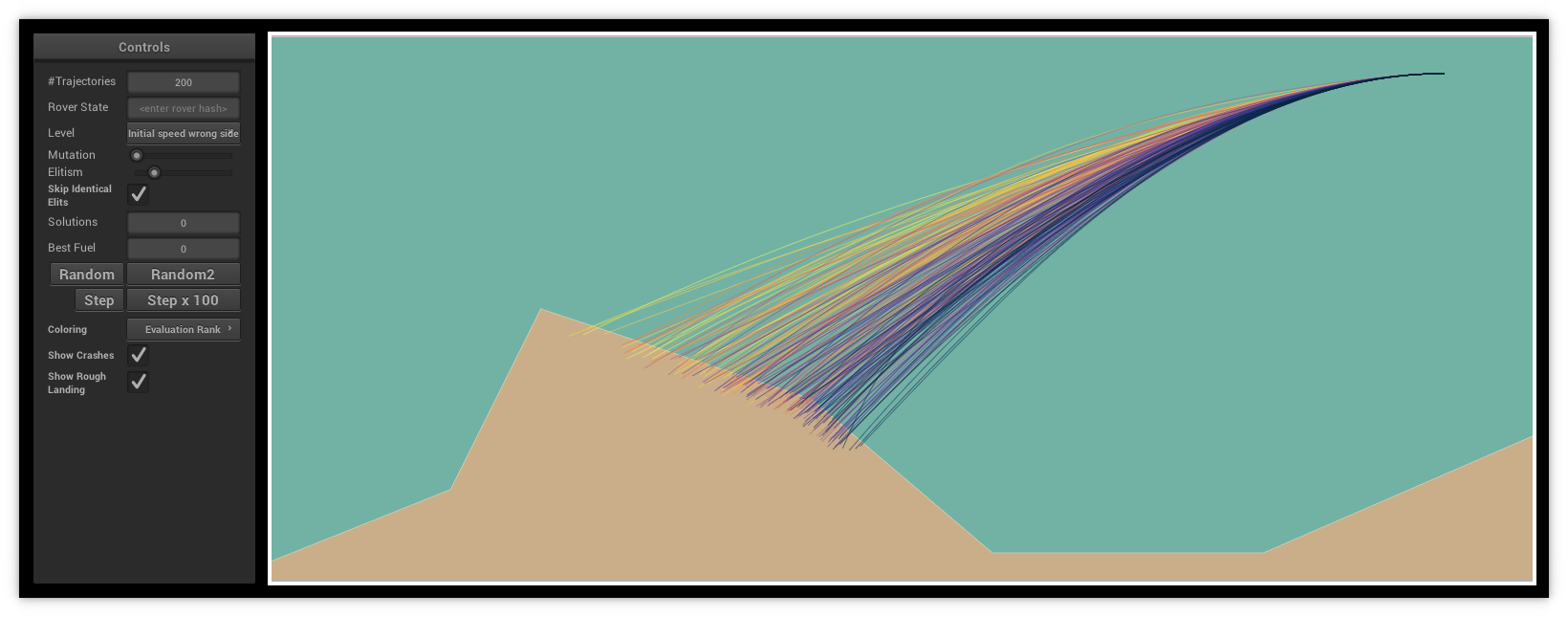

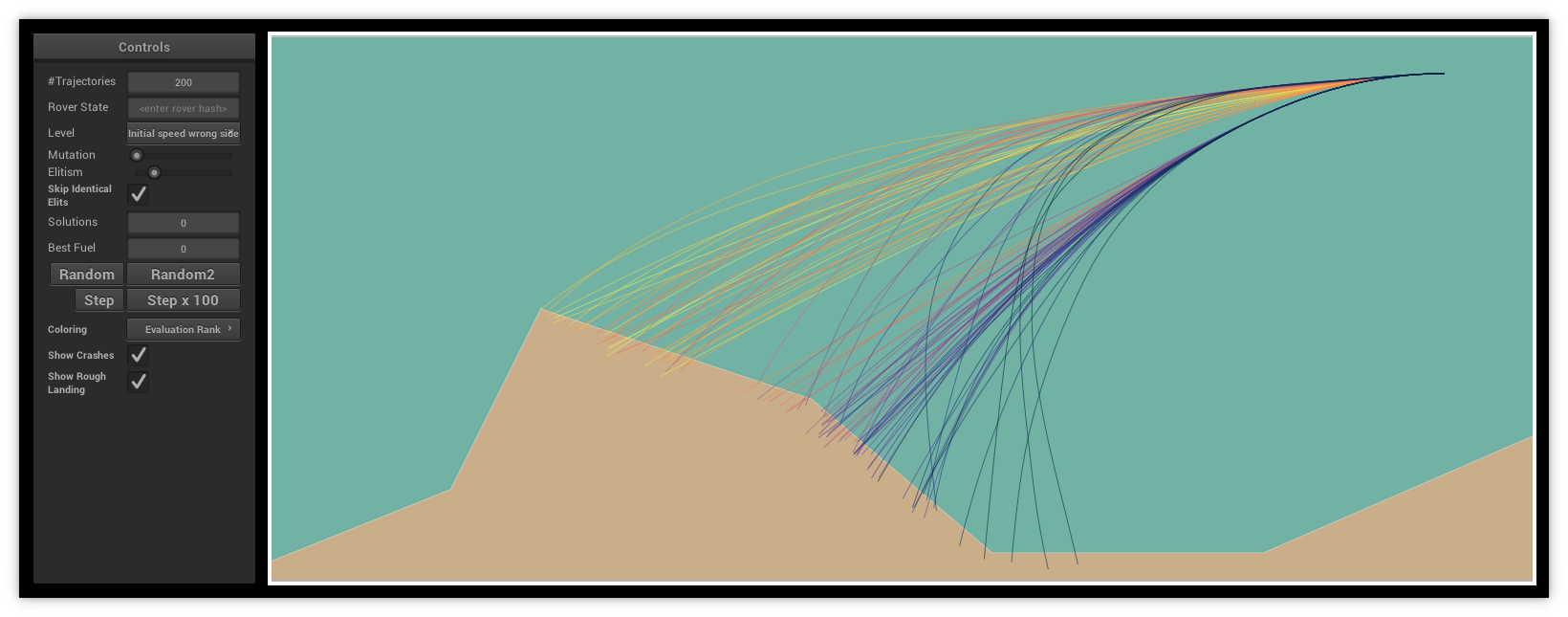

First, I noticed that my initial population needed to be more satisfying. My randomly generated trajectories did not spread wide enough to cover much of the search space and quickly guide the subsequent populations in promising directions. From a lander state, there are at most 93 possible commands (31 rotations times 3 thruster variations). I divided the initial population into buckets, each bucket starting with ten times the same command/gene, then randomly extended until reaching the ground. Look below for the effects of such a modification.

Then I optimized the update method of the lander data structure. Since there are only 93 possible commands, we can precompute an acceleration table and use that table to simulate the lander reaction to a command without calling trigonometry functions. It did improve my score, but not by much. I checked what happens if I gave the bot twice the time to perform its search, and the results were not sensibly better. There was no need then to try to optimize the code more.

I tried additional tricks, but most did not improve my score. I'm ashamed of the tricks that worked, and I want to keep them to myself; they are not that smart, I am sure you can find them yourself. My final score is 2475, rank #24, at 98.6% of the best score.

Conclusion

This was a fun side project. I had fun learning and applying genetic algorithms to that optimization game. I'm still surprised by what we can achieve with only mutation and crossovers. The code is straightforward and does not contain advanced trajectory optimization or navigation knowledge. I plan to try again to use genetic algorithms for other problems and get more familiar with them. If you also have issues with genetic algorithms, please give them a try on that game!