In May 2021, there was a programming contest on CodinGame. I looked it forward, as it was the occasion to measure the progress I made this year. My objective was to finish in the 200 first contestants. After the final run, I ended in 71st place, which I consider quite an achievement compared to my previous ranks (651 in the Spring 2020 contest and 251 in the Fall 2020 contest). I enjoyed this contest a lot!

Competitive programming in a limited time can be overwhelming. You need to know yourself well to make most of the remaining time while mitigating your weaknesses. In the past, I tended to over-engineer useless details instead of focusing on what could sensibly improve my bot, mostly because I had no idea what to do. Also, I tried to overcome my lack of knowledge or confidence by applying new algorithms heard in the CodinGame chat without stepping back a little and think ahead. As a result, I overlooked key features of games, missed some bugs inserted early in the code base, ended frustrated about my final rankings, and did not have a pleasant overall experience.

For this contest, I decided to organize myself better to improve my ranking and have fun. This article describes the steps I went through during the contest, the decisions I took, and the rules I followed. Hopefully, it could give you ideas to try and find what works best for you.

1. Analysis of the Game and Going Through the Wood Leagues

When a contest starts, you may be tempted to write a lot of code to have as soon as possible a very clever bot. I know for sure that I would have performed poorly if I tried to do so. Instead, I analyzed the game and sketched my plan for the duration of the contest. I believe that conceiving this plan and trying to stick to it for the contest is the reason I achieved my objective.

Since the game rules are simplified in the wood leagues, I consider it is best to start by adding the minimal lines of code needed to be promoted to the bronze league. That way, you quickly have access to the full set of rules to plan your contest. For this particular contest, there was not much to do to reach bronze league.

The contest is a turn-based two-player board game where players play simultaneously. You can read the rules in the CodinGame IDE and find the original board game it is based on at the Blue Orange website. There is no fog of war nor incomplete information. Thus I was relieved as I tend to perform weakly with such features 😌.

The game seemed to be a good fit for heuristics, which is not my cup of tea. As an exercise, I managed to reach legend league in Tron with a heuristic-only bot, where I score possible moves and select the best one. It took me multiple weeks to design such heuristics, and I never tried again. I am more comfortable with search algorithms, and I thought I could successfully apply such algorithms to this game. Thus, I ruled out heuristic-based AI for this contest but took a mental note to experiment with heuristics later. I believe injecting some domain knowledge into my search algorithms thanks to heuristics could improve my bots.

Simply put, a search algorithm will explore the space of possible game states from the current one. A transition between game states occurs after a couple of actions, one for each player, during a turn. Computing the next state given a state and a couple of actions is often referred to as simulation on CodinGame, as it simulates the effects of the actions in the game.

The search algorithm will then chose the action that led to the most promising future states. As expected for a contest, the branching factor of the game is high (i.e. the set of next states from a given state is large). Thus, exploring all the state space is impractical. I thought I would need some pruning rules to reduce the branching factor and explore only the most promising paths. To ensure pruning rules do not decrease the bot strength, I decided to rely on a local arena. All improvement ideas are to be validated by the win rate against previous bot versions. Since the players play simultaneously in this game, I was unsure how to handle it in the search algorithm. I decided to consider that each player plays one after the other one. I believed it would not matter for my top-200 objective.

Simulating the game seemed easy, but I wanted to validate the simulation code.

A bug in the simulation part could lead to unstable win rates and make real improvements look like wrong ideas as the win rates remain the same or drop once implemented.

Such bugs often occurred in the past and left me completely clueless about what I was doing wrong.

So I wanted to have a mechanism to validate this code during the contest.

Some time ago, I read a post on the CodinGame forum _Royale saying that he relied on the referee to validate its code.

The principle is simple: we play many games inside the arena, next we analyze the replays to extract the states before and after actions, then we have a set of unit tests to validate our simulation code.

I have settled for a Monte Carlo algorithm until I reach the gold league, then it would be most likely an MCTS. I am familiar with such algorithms and thought they would be a good fit for me to reach top-200. Since I tend to rely a lot on performance to overcome my lack of heuristics, the game state should allow fast construction of the possible actions set and fast simulation. I came with a bitboard representation of the game that you can find in other post-mortems. I squeezed the game state into 64 bytes and kept the same representation for the whole contest duration. Below is the sketch of my representation.

struct Action { ... }; // 2 bytes in total

struct State {

State(const State& other) noexcept { load(other); }

void load(const State& other) noexcept;

void play(Action actions[2]);

...

}; // 64 bytes in total

struct PlayersActions {

Action actions[2][...]; // loaded actions for both players

uint16_t counts[2]; // number of possible actions per player

void loadAll(const State&) noexcept; // no action pruning

void load(const State&) noexcept; // pruned actions

void pick(Action*) const noexcept; // randomly pick 2 actions, 1 per player

};

Plan Summary:

- implement

PlayersActions::loadAll - validate

PlayersActions::loadAllby comparing the results with the actions given by the referee at the beginning of a turn - implement

State::play - validate

State::playby parsing replays - implement a Monte Carlo algorithm to reach the silver league

- build a local arena

- benchmark

State::playandPlayersActions::loadAllto find performance improvements - validate the improvements with the local arena until I reach the gold league

- implement

PlayersActions::loadand test the pruning in the local arena - switch to a paranoid MCTS

- tune the MCTS and the pruning methods until the end of the contest

Rules of Conduct:

- avoid using heuristics as I am likely to fail

- try first methods you know the best

- focus on what could improve the bot the most

- validate the code

- try and validate only one improvement at a time

2. Going from the Bronze League to the Gold League

This section describes steps 1 to 9 of the aforementioned plan. Steps 1 and 2 were a piece of cake. By sorting the results and the answers given by the referee, we can find and report differences. When differences are found, I make the bot crash after reporting them. That way, by fetching the replays of matches in the arena, I can have roughly 100 matches of 100 turns i.e. ~10k validation tests. I like this validation method as I do not have to write unit tests myself.

For steps 3 and 4, I failed to adhere strictly to the plan. Finding a solution to validate the simulation by parsing replays caused me some issues. I preferred to ignore it and I almost missed my goal: I felt urged to progress in the competition and did not want to take the time to validate this part correctly. I learned my lesson well and I always work according to the original plan now: no more shortcuts 😅. I did this step after I switched to an MCTS (step 9) which allowed me to recover in time.

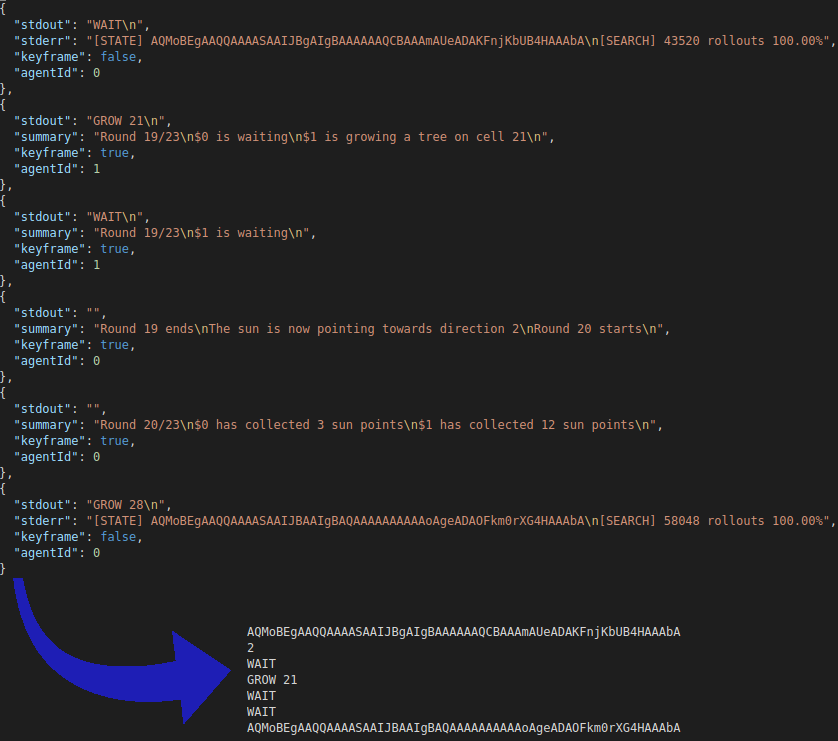

State::play is expecting one action per player, wait actions are added for players already waiting.

The replays for this game contain different kinds of frames. Some represent the start of a new day, others are for the sun collecting step at the beginning of each day, and the remaining ones are for the answers given by player bots. I focused only on the latter type of frames. Thanks to them, we can gather the sequence of actions from the frames relative to bot answers. Next, we need to extract the game states from replays to test the simulation. At each turn our bot is playing, we can output the game state. The issue here is that our bot is not playing every turn: after our bot waited, it will not receive any update until the beginning of the following day. I solved this by slicing the sequence of actions at each frame my bot answered. At the beginning of each slice, I thus have the resulting state of the actions contained in the previous slice. I made a python script that extracts these slices from replays and feeds them to my simulation validator. This allowed me to find quickly three bugs I had in the simulation part and pushed me from top-400 to top-100.

A minor drawback of that method is that I cannot validate the end game code since the bot does not output a frame once the game ends. Instead, I output a prediction of the final state and the final score when my bot is the last one to wait on the final day. I could then validate the code by playing in the IDE.

With steps 1 and 3 out of the way, having a decent Monte Carlo bot (step 5) was quite fast, despite the bugs I had in the simulation part.

Writing the local arena took more time 😁.

I used the same kind of arenas Agade wrote (see the ones for Fall Challenge 2020 and Ghost in the Cell).

However, for games with more than 50ms turns, I tend to have issues with this kind of arena with multiple threads.

I suspect this is because I have stalling in system calls that I do not take into account when measuring the answer time.

The arena thus considers a bot took too long to answer and declare the other one the winner.

I had to use only 3 threads to not have this issue on my computer for this game.

I will experiment with other ways of writing arenas for the next contest.

Thanks to the arena as well as a driver program to profile the execution of a turn, I quickly identified hotspots in the code. I used this information to iteratively remove computations that could have been precomputed. As expected, the number of complete rollouts per turns increased a lot, while the win rates against previous versions increased only a little. To significantly increase the win rates, I had to play with the action pruning done in this method (step 9).

3. Going to the Legend League

I decided to switch to an MCTS algorithm earlier than I initially thought. The rationale behind this decision was that a Monte Carlo algorithm keeps computing the actions on the same game states at the first depths. Since computing the actions was what cost me the most CPU time, it made sense to do it less often and reuse the results. An MCTS algorithm allows that by storing available moves in the nodes. Also, since I had bugs in my simulation code, my action pruning experiments led to dead ends and I was lacking alternatives to reach my objective 😒.

I decided to make a paranoid MCTS: my bot plays first, then the opponent plays, when both players are active, instead of playing simultaneously. As a result, the opponent already knows what our bot played and can counter it. Hence the name paranoid, as our bot considers the opponent knows in advance what our bot will do. At the end of the contest, I tried a DUCT MCTS, but I failed to optimize it enough to beat my paranoid MCTS. Thus my MCTS is quite similar to the one I made for Langton's Ant. Its only particularity is to update the state after going through two depths: one for me and one for the opponent. That way I could compute available actions only once to build all the nodes for the next two depths. See for example the selection code below:

Action actions[2];

while( !state.finished() ) {

auto current = nodes[ node_index ];

if( current.child_count == 0 ) break;

NodeSelecter selecter1{ current };

for( uint16_t i = 0; i < current.child_count && !selecter1.finished(); ++i )

selecter1.add( current.left_child + i );

auto& p0 = nodes[selecter1.best_node_index];

NodeSelecter selecter2{ p0 };

for( uint16_t i = 0; i < p0.child_count && !selecter2.finished(); ++i )

selecter2.add( p0.left_child + i );

node_index = selecter2.best_node_index;

actions[0] = p0.action;

actions[1] = nodes[node_index].action;

state.play(actions);

}The win rates of my MCTS were noticeably better than those of my Monte Carlo bot. Still, something was odd. When discussing with the helpful people of the french channel in CodinGame's chat, I remarked that I was doing the same things as others. However, those people were far higher in the ranking, whereas I had much more rollouts per turn than them. Also, when trying some pruning methods I believe were clever, the results were disappointing. I easily recognized the symptoms: I had bugs in the simulation code 😥. I spent the night finally doing step 4 and reached the legend league 😂.

During this contest, I had much to do during the day at my new job.

So I worked during nights on the contest and I ended quite tired.

After reaching legend, I only had the strength left to try some pruning methods and submit another version before recovering from exhaustion (^_^).

I am sure there are still many improvements to do in the pruning, exploration, and evaluation/backpropagation parts of my bot.

In particular, my bot considers all victories to be equal and does not try to maximize the final score.

It will be nice to tinker with these parts one day.

Conclusion

It was a nice contest, I liked the game, and the arts were lovely. There were many valid approaches to the game, making it very interesting for learning purposes. I think I will capitalize on it to make me acquainted with heuristic methods. I cannot always rely on MCTS 😆.

Sketching a plan of action for the contest improved my efficiency. The plan prevented me from being side-tracked or procrastinating with useless details when I am clueless about what to do. Although, I am sure it would do me good if I could stick to the plan next time. The tooling scripts and code I developed were quite helpful; I need to continue to invest in it. I believe I found a way to organize myself during contests that suits me.

Thank you CodinGame for having such contests and kudos to reCurse for his crushing victory.